Loving and Learning from Children with Special Needs

I’m coming to the end of a one-block (seven-week) BYU class on special education for elementary school students. Not only have I learned more about various disabilities—cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, epilepsy, ADHD—I’ve also learned to see the great potential in children with special needs.

Before I took this class, I thought differently about teaching children with special needs. I was nervous to help students with learning disabilities, physical disabilities, and emotional disturbance—and to tell the truth, I thought that it would be difficult to include them in my general ed class with the other students.

In class, we shared thoughts on the question, what stops us from being open to learning from those with special needs?

Some eye-opening myths about disabilities we discussed include:

- MYTH: Individuals with disabilities are always dependent and always need help.

- FACT: We don’t always have to step in—we need to learn when to intervene, when to ask if these individuals want help, and when to give them time to struggle through a task.

- MYTH: Individuals with disabilities should be treated differently.

- FACT: If we keep treating these individuals differently, they will have trouble learning to be integrated in the classroom or into society.

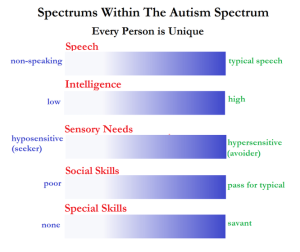

- MYTH: Individuals with disabilities are all the same.

- FACT: We can’t believe stereotypes—there is a wide range of abilities. For example, the autism spectrum includes abilities from nonspeaking to typical speech.

- MYTH: A person’s disability defines who they are as an individual.

- FACT: These individuals have personalities and preferences. We need to think of these individuals’ assets and not complain about the challenges of interacting with them.

Throughout the class, my attitude changed and my bag of tricks grew. Guest speakers touched my heart when they expressed their own challenges or their work with individuals with disabilities. I cried more than once.

I learned many ways to accommodate for students with special needs—including ways to use materials, position the environment, instruct in various subjects, and provide behavior contracts. The LDS Church offers great guidelines on adapting lessons to help individuals with disabilities as well.

I learned many ways to accommodate for students with special needs—including ways to use materials, position the environment, instruct in various subjects, and provide behavior contracts. The LDS Church offers great guidelines on adapting lessons to help individuals with disabilities as well.

Volunteering with a student created the biggest adjustment in my thinking. Twice a week, I visited a local elementary school and worked with an upper-grade student during math. Although he was socially proficient—and even quite comical with his jokes—the academics side just did not come easily for him.

As I saw the difficulties this student faced in accessing the content and using the procedures that his peers caught onto so quickly, my heart went out to him. Frustration also came when I asked questions to help him understand or to encourage him to explain his thinking and we both ended up confused. Laughter helped us bond. I discovered that he thought really well about problems when we used real-life contexts, like candy or pizza or iPads or mountains. I’m not sure how much he gained from our interactions, but I gained a lot of insight.

Instead of dreading the responsibility of teaching individuals with disabilities, I’m looking forward to the opportunities. Building an inclusion classroom to help all students succeed is now my goal.

—Leah Davis Christopher, Stance

In my next post, read excellent tips for cracking the code behind misbehavior.

You must be logged in to post a comment.